The life-cycle, exploitation and use of Ostrea edulis: A literature review.

Lisa Mead.

This literature review is intended to give an overview of the information available from books, magazines, newspapers and the internet relating to Ostrea edulis, also known as the European Flat Oyster or Native Oyster.

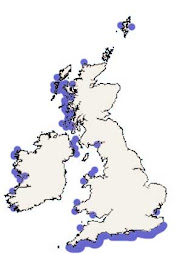

The Marine Life Information Network for Britain and Ireland (MarLIN) has an accessible and informative website which contains several pages dedicated to O. edulis. The website itself is simple to navigate and species can be found easily using the search function or within the appropriate phylum. The information about O. edulis is also well presented and divided into the following pages with clear tabs: Basic Information, Taxonomy and Identification, General Biology, Habitat Preferences and Distribution, Reproduction and Longevity, Sensitivity and finally Importance. Each of these areas are provide a good depth of research; the Habitat Preferences section contains maps, details of British distribution as well as where O. edulis can be found naturally worldwide: “...Widely distributed around the British Isles... The main stocks are now in the west coast of Scotland, the south-east and Thames estuary, the Solent, the River Fal, and Lough Foyle... Found naturally from the Norwegian Sea south through the North Sea down to the Iberian Peninsula and the Atlantic coast of Morocco...”[1].

‘A Student’s Guide to the Seashore’ is a comprehensive guide and includes two pages of information about Ostrea edulis. It contains a simple guide to “help those readers who are unable initially to assign an organism to its correct phylum or class”[2]. This, combined with the Index of latin names at the back, makes it easy to locate relevant information about O. edulis, whether you have found a species and want to identify it, or are looking for further information. Although there is only one black and white drawing of O. edulis included, the accompanying information describes shape, size and colour in some detail. References are made to predators such as Crepidula fornicata (Slipper Limpet) which can smother oyster beds and Asterias rubens (Common Starfish) which “prey on a wide range of food items including molluscs...[A. rubens are]...important predators of oysters”[3]. There are page numbers along with these references so further information about these species can be gained. Also included is information on the distribution, breeding and longevity of O. edulis.

Two reference books that provide information about O. edulis are ‘The Encyclopedia of Shells’ and the ‘Guide to Seashores and Shallow Seas’. Both books contain limited information about O. edulis, giving only a brief description of the appearance and distribution. However, ‘The Encyclopedia of Shells’ is a more useful resource for information on the structure of bivalves and gastropods with clear labelled diagrams, as well as general information on the Mollusca phylum. Both books would be suitable for identification and classification, although the ‘Guide to Seashores and Shallow Seas’ would be more helpful as a practical guide, being small enough to take to the beach or shore to identify species, as well as including clear colour pictures and simple descriptions of each species. In both cases, information is easy to access; species of the same class are grouped together, plus in ‘The Encyclopedia of Shells’ two separate indexes list both common and latin names.

For photographs of O. edulis, ARKive is an excellent website. Describing itself as “a unique collection of thousands of videos, images and fact-files illustrating the world's species”[4], each species has information and images which can be accessed easily using the search function on the home page. O. edulis had only three photographs, but the images were of very good quality as they are donated to the website by (among others) professional film-makers, photographers and conservation organisations. Some species had very few images, while others such as Sepia officinalis (common cuttlefish) had 12 photographs as well as 8 videos. As a resource for multimedia, this website offered more practical use than the black and white drawings in books such as ‘A Student’s Guide to the Seashore’; the images were more varied as they had come from a range of sources and could be copied and saved in high quality. In addition to the images, the text information is easy to understand and divided into sections down the side of the species’ page, each of which can simply be clicked on to bring up the relevant information.

‘Seashore’ is a “...comprehensive, authoritative account of the natural history of the seashore...”[5] and contains a wealth of information. However, as the book is divided into chapters dealing with a topic such as “life on the seashore” as opposed to grouping species by class or even phylum, information is comparatively difficult to access. The single reference to O. edulis from the glossary relates to reproduction: “Ostrea edulis, is one of an interesting minority of bivalves that further reduces reproductive loss by brooding its eggs within the mantle cavity”[6]. It then goes on to explain how O. edulis fertilise their eggs within the mantle cavity and do not shed the larvae until they are in the advanced stage, giving them a better chance of survival. A comparison is made to other bivalves, where fertilisation occurs in the open after the eggs and sperm have been released.

For an example of the local use of O. edulis ‘Around Britain with a Fork’ is an article about an oyster fishery in West Mersea, Essex. The article talks specifically about the work of oyster fishermen Richard Haward and his son Joe Haward: the fourth and fifth generation to work on the river Blackwater. It mentions the difficulties of growing O. edulis, which is “prone to all manner of ailments, susceptible to the warming of water, disturbance, pollution and other modern hazards”[7]. It also mentions the need for and method of purification: “...they spend a few days being cleaned in an ingenious system of tanks purified by ultraviolet light...”[8] as well as discussing the local businesses, restaurants and markets where the oysters are sold.

Information about O. edulis further afield is given in ‘Bottomfeeder’, by Taras Grescoe. It is an account of his “round-the-world trip as he eats his way from the bottom of the food chain to the top...[and]...explores the impact we are having on sea life by overfishing...”[9]. Although not all the book is relevant, the chapter titled ‘Chesapeake Bay and Brittany – Oysters’ contains some information about O. edulis, as well as another oyster: Crassostrea virginica (American Oyster). The chapter is easy to find from the contents page at the front of the book, but you need to read the whole chapter to find the reference to O. edulis as there is no index at the back. The chapter discusses the history of O. edulis and his experiences in France tasting oysters and finding out more about the farming methods as well as over-fishing. It also goes into some detail about the problems faced in Chesapeake Bay for both the oyster population and the quality and diversity of the bay itself from factors such as overfishing and excess nitrogen from fertiliser run-off.

A short article in the Shellfish News entitled ‘Farming Depth of Native Oysters’ presents the findings of four scientists in Croatia who were studying the affect cultivation depths of O. edulis has on survival and growth. The article explains their research and sampling methods and records their results: “...total weight gain and soft tissue weight gain were the highest for groups cultivated in the middle of the water column...”[10]. A second relevant article within the same issue of the Shellfish news was entitled ‘The native oyster in Scotland’ and discusses the Species Action Framework (SAP) launched by the Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH). O. edulis has been included in the SAP because it is a species which has social and economic benefit. The second article was better referenced than the first, giving the web address for the SNH, which is in itself another excellent source of information. O. edulis is easy to find on the SNH website using the search function in the top corner and includes sections including species background, why O. edulis is on the action list, habitat, history of decline, action up to April 2007 and relevant links. The links are particularly useful and include MarLIN, UK Biodiversity Action Plan, ARKive as well as a “latest news” section.

Information on the current status of and proposed actions regarding to O. edulis can be found on the website of the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP). The website has a page of information for each species and the text for O. edulis is divided into clearly headed sections. This is not an identification or general website, the information given deals specifically with factors causing a decline in abundance, current national legislation or bye laws which affect the species as well as proposed action. The information is detailed and references relevant legislation and directives. The report reinforces Campbell’s argument in ‘A Student’s Guide to the Seashore’ that C. fornicata are a predator to O. edulis and explains in more detail the reasons why, but goes on to discuss many more predators and parasites (including Urosapinx cinerea and Bonamia ostreae) which have had an impact on O. edulis populations, not mentioned in ‘A student’s Guide to the Seashore’.

The Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS) wrote a report for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) in 2005 which references the Biodiversity Action Plan mentioned above. A study into stock regeneration of O. edulis in the United Kingdom, it is “A Review of Biological, Technical and Economic Feasibility”[11] and goes into great detail. The report has a clear contents page so relevant information is easy to pinpoint and the findings are divided under the following headings: Biological Factors, Technical Requirements, Regulatory Framework, Economic Analysis, Current Status and Attempts at Restoration. There is an awful lot of useful information contained within the report, a good example is the Biological Factors section which is subdivided thus: Introduction (General information on O. edulis, including fertility and life cycles), site selection (detail on how “A range of physical, biological and chemical factors will influence survival and growth of oysters”[12]), genetics, disease (including information about Bonamiasis, “...the one major disease of significance present in oyster stocks in the UK...”[13]) resistance to disease, pests and chemical contaminants. All findings are supported by scientific research, which is fully referenced within the report, although some of this research conflicts with more recent information I found. Under the sub-heading ‘Site Selection’, the report looks at existing research into population growth of O. edulis at various depths and states “...there is very little information to show if there is a preferred depth”[14]. The report then goes on to review the research of Diaz (2001) who “found no difference in growth performance of oysters suspended at different depths”[15]. This directly conflicts with the information gained from the 2008 Shellfish News article ‘Farming Depth of Native Oysters’, which suggests that the middle of the water column is the most productive area for O. edulis, allowing the largest soft tissue weight gain.

I found information about O. edulis in books, articles, reports and on internet sites. Reference books such as the seashore guides contain easy to access basic information about the species and some, such as the ‘Guide to Seashores and Shallow Seas’ were also helpful as identification books. Many websites exist that give more detailed information on particular species, including O. edulis, and the MarLIN website even gave maps of distribution based on survey results. Hundreds of magazine and newspaper articles have been written worldwide which mention O. edulis, though most have limited biological detail. The most detailed and useful source I found was the CEFAS report, which divided findings into sections and sub-sections so taking relevant information from it was simple. There is a wealth of information available about O. edulis, whether you are simply trying to identify a specimen, or looking for more specific research.

[1] MarLin Website http://www.marlin.ac.uk/species/adult_distrib_Ostreaedulis.htm

[2] Fish J.D. and Fish S. 1996 ‘A Student’s Guide to the Seashore’ Cambridge Press, Page 10

[3] Fish J.D. and Fish S. 1996 ‘A Student’s Guide to the Seashore’ Cambridge Press, Page 443

[4] ARKive Website www.arkive.org

[5] Hayward P.J. 2004 ‘Seashore’ HarperCollins, Back Cover

[6] Hayward P.J. 2004 ‘Seashore’ HarperCollins, Page 86

[7] Haward R. cited by Fort M. ‘Around Britain with a fork’ The Guardian, Saturday December 16th 2006, Page 69

[8] Fort M. ‘Around Britain With a fork’ The Guardian, Saturday December 16th 2006, Page 69

[9] Grescoe T. 2008 ‘Bottomfeeder’ Macmillan

[10] Zrncic S et al. 2008 ‘Farming depth of native oysters’ Shellfish news Issue 25 Page 57

[11] CEFAS Report: ‘A feasibility study of native oyster (Ostrea edulis) stock regeneration in the United Kingdom’, Page 1

[12] CEFAS Report: ‘A feasibility study of native oyster (Ostrea edulis) stock regeneration in the United Kingdom’, Page 21

[13] CEFAS Report: ‘A feasibility study of native oyster (Ostrea edulis) stock regeneration in the United Kingdom’, Page 26

[14] CEFAS Report: ‘A feasibility study of native oyster (Ostrea edulis) stock regeneration in the United Kingdom’, Page 21

[15] Diaz (2001), paraphrased in the CEFAS Report: ‘A feasibility study of native oyster (Ostrea edulis) stock regeneration in the United Kingdom’, Page 21

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment